- *Corresponding Author:

- Nongbe Medy Camille

National Laboratory for Quality Testing, Metrology and Analysis (LANEMA), Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire

E-mail: medycamille@gmail.com

| Date of Received | 14 September 2025 |

| Date of Revision | 15 September 2025 |

| Date of Accepted | 15 November 2025 |

| Indian J Pharm Sci 2025;87(6):233-244 |

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms

Abstract

Soil contamination by heavy metals represents a major environmental challenge in tropical regions due to their toxicity, persistence, and bioaccumulation in ecosystems. This study investigates the potential of the tropical fern Nephrolepis biserrata for the phytoremediation of soils artificially contaminated with chromium, copper, zinc, and arsenic. Plants were cultivated for 56 d in moderately acidic, low-salinity soil and analysed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry to quantify metal accumulation in roots and shoots. Results revealed strong bioaccumulation of zinc and copper, with bio concentration factors reaching 33.7 and 19.0 at 20 mg/kg, confirming hyper accumulation behaviour. Chromium showed moderate uptake, whereas as was weakly accumulated. Kinetic modelling indicated that chromium followed a first-order model, while copper and zinc fitted a pseudo-second-order model (R2>0.96), suggesting chemisorption through specific interactions with cell wall functional groups. Langmuir isotherms provided the best fits (R2>0.96), highlighting monolayer adsorption on homogeneous sites. Thermodynamic analysis demonstrated spontaneous (ΔG°<0), exothermic (ΔH°<0), and entropy-increasing (ΔS°>0) processes, confirming favourable metal-plant interactions. Overall, Nephrolepis biserrata emerges as a promising candidate for selective phytoremediation of tropical soils, particularly effective for copper and zinc contamination.

Keywords

Phytoremediation, heavy metals, Nephrolepis biserrata, modelling, tropical soil

Soil contamination by heavy metals has become one of today’s major environmental concerns, due to the toxicity, persistence, and bio accumulative nature of these elements in ecosystems[1,2]. Although these metals naturally occur in trace amounts in soils, they are introduced at concerning concentrations through anthropogenic activities such as mining, industrial effluents, urban waste, and excessive use of agrochemicals[3,4]. Chromium (Cr), Copper (Cu), Zinc (Zn), and Arsenic (As) are among the most frequently found metals in tropical soils, where their chemical properties allow them to persist, affecting soil fertility as well as plant, animal, and human health[5,6].

In tropical environments, the mobility and bioavailability of these metals are strongly influenced by the soil’s physicochemical properties-particularly pH, organic matter content, texture, and electrical conductivity[7]. Their accumulation in plant biomass represents an entry route into the food chain, with proven health effects such as neurotoxicity, cancer, and metabolic disorders[8,9]. In response to this threat, various remediation strategies have been developed, but many remain costly, complex to implement, and poorly sustainable in tropical contexts[10,11].

Phytoremediation, on the other hand, stands out as a promising ecological alternative, exploiting the natural ability of certain plants to absorb, accumulate, or stabilize pollutants in soils[12,13]. Among potentially interesting species, tropical ferns have recently attracted attention for their resistance to environmental stress and their ability to grow in nutrient-poor substrates. Nephrolepis biserrata (N. biserrata), in particular, is notable for its ecological plasticity, rapid growth, and still little-explored phytoremediation potential[14,15].

Previous studies have shown its ability to accumulate metals such as Pb, Cd, Cu, and As in polluted mining areas[16,17], but little data exists on its ability to selectively bio accumulate Cr and Zn, nor on the mechanisms underlying this accumulation in tropical soils. Furthermore, very few studies integrate comprehensive kinetic, isotherm, and thermodynamic modelling of these processes in such contexts.

This study aims to assess the bioaccumulation behaviour of N. biserrata toward Cr, Cu, Zn, and as in artificially contaminated tropical soil under controlled conditions. It is based on an integrated approach combining bio concentration dynamics analysis, kinetic modelling (first-order, pseudo-secondorder), isotherm modelling (Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin models), and thermodynamic modeling (ΔG°, ΔH°, ΔS°), in order to better understand the physicochemical mechanisms involved in metal adsorption and storage. The results will help position N. biserrata as a potential plant species for selective and sustainable phytoremediation of contaminated tropical soils.

Materials and Methods

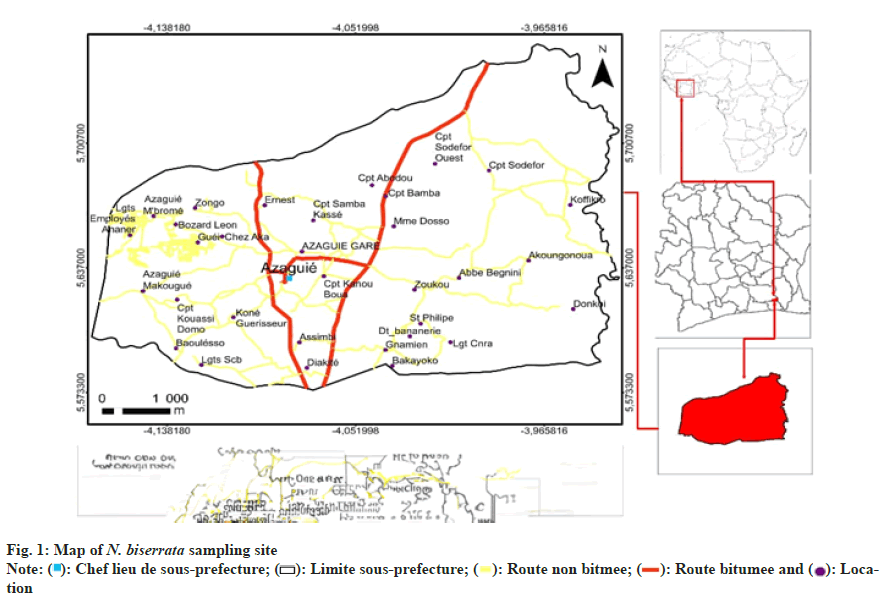

Plant material: The plant material used in this study consisted of N. biserrata plants and soil collected from an undisturbed site located in the village of Abbè- Bégninou, in the municipality of Azaguié, southern Côte d’Ivoire. This site, located between longitudes 5°30′W and 5°50′W and latitudes 3°55′N and 4°10′N, is about 40 km from Abidjan. It is characterized by low anthropogenic pressure, ensuring the ecological quality and low initial contamination of the plants and soil sampled (fig. 1).

The fern N. biserrata, widely distributed in tropical wetlands, was selected for its recognized phytoremediation qualities, including rapid growth, robustness, and adaptability to diverse environments. Young plants were carefully uprooted, washed with distilled water to remove soil residues, and transferred to the laboratory for experiments. In parallel, soil samples were manually collected in polypropylene bags. These samples were air-dried for 5 d, then sieved and freed of organic debris before use in controlled culture experiments.

Experimentation

Plant cultivation: The experiment was conducted under semi-controlled conditions, sheltered from rain, in a greenhouse designed to simulate a tropical environment. The experimental setup consisted of cultivation in 5 l pots (height: 12 cm), each containing 1 kg of soil, arranged in triplicate for each treatment. The soil, collected in Azaguié (Côte d’Ivoire), was artificially contaminated using standard solutions of heavy metals (Zn, Cu, Cr, and As) at increasing concentrations of 20, 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg. Contamination was carried out before potting to ensure optimal homogeneity of the metal load in the substrates.

Young N. biserrata plants, collected from the undisturbed site in Abbè-Bégninou (Azaguié), were transplanted into the pots containing the different treatments. After transplantation, the plants were grown for 8 w, during which regular observations of their growth were made.

The cultivation conditions were rigorously controlled throughout the experiment. Uniform watering with distilled water was carried out, thus avoiding any external contamination. This protocol made it possible to standardize growth conditions, ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of results related to heavy metal bioaccumulation.

Soil physicochemical characterization:

The soil sample used in this study was analysed according to standardized protocols. The following parameters-pH (water and KCl), electrical conductivity, dissolved oxygen, moisture content, organic matter, and Total Nitrogen (TKN)-were determined according to AFNOR standard methods (AFNOR, 2001).

Sample preparation for Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis:

PSoil and plant samples were prepared according to protocols adapted for heavy metal analysis. For plant material, the roots and leaves of N. biserrata were separated, carefully washed with distilled water, then dried in an oven at 80° until constant weight. The dried samples were ground into a homogeneous powder. A mass of 0.5 g of this powder was subjected to acid digestion in an autoclave using 2 ml of Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and 5 ml of Nitric acid (HNO3). The digest was made up to 50 ml with ultrapure water .

For soil analysis, 1 g of dried sample was digested according to the standard EPA 3050B method, using an acid mixture of nitric acid (HNO3) and perchloric acid (HClO4). The digested samples were filtered, and the filtrates were transferred into 50 ml volumetric flasks with ultrapure water for metal analysis.

Determination of heavy metal concentrations by ICP-MS:

The concentrations of Cr, Cu, Zn, and As were quantified in the digested samples using an ICP-MS. The results were expressed in mg/kg of dry matter. Concentrations were calculated according to the following equation:

Cmesured=(Vfinal×Csolurion)/msample (1)

Where, Csolurion is the concentration measured by ICPMS (mg/l), Vfinal is the final volume after digestion (L), and msample is the mass of the dry digested sample (kg).

Calculation of bio concentration factors: Bio concentration factors were calculated for each metal using the following formula:

BCF=CMP/CMS (2)

Where, CMP is the concentration of the metal in plant tissues (mg/kg dry weight), and CMS is the total concentration of the metal in the soil (mg/kg dry weight).

Kinetic modelling: First-order model fitting: This model assumes that the adsorption rate is proportional to the residual concentration of available sites. Using the experimental data and the linearized kinetic equation:

Log (qe-qt)=log (qe)-k1/2.303-t (3)

Pseudo-second-order model fitting: The pseudo-second-order model is based on the assumption that adsorption is governed by chemical interactions (covalent or surface bonding). The linear form of the equation is:

t/qt =1/(k2qc2 )+t/qe (4)

Adsorption isotherm modelling: Langmuir model: This model assumes monomolecular adsorption on a homogeneous surface with a defined maximum capacity:

Ce/qe=1/(KLqmax )+Ce/qmax (5)

Where qe is the amount adsorbed at equilibrium (mg/g), Ce is the equilibrium concentration in solution (mg/g), qmax is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g), and KL is the Langmuir constant (l/mg). Freundlich model: This empirical model assumes multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface:

log(qe)=log(KF+1/n log(Ce) (6)

Where KF is the adsorption capacity constant (l/mg), and n is the adsorption intensity (adsorption is favourable when 1<n<10).

Temkin model: This model accounts for the linear decrease in adsorption heat as surface coverage increases:

qe=BlnA+BlnCe avec B=RT/b (7)

Where A is the Temkin constant related to adsorption capacity, b is the constant related to adsorption heat, R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K), and T is the absolute temperature (K).

Thermodynamic modelling: Thermodynamic parameters were calculated from the equilibrium constant Kc, determined at different temperatures (298, 308, and 318 K), using the following relationships:

Equilibrium constant: Ke=qe/Ce (8)

Where qe is the amount adsorbed at equilibrium (mg/g), Ce is the residual concentration in solution (mg/l).

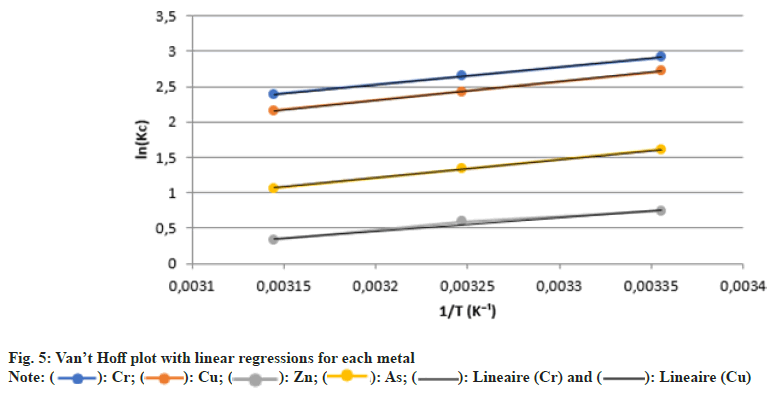

Van’t Hoff equation: lnKC=-(ΔH°)/RT+(ΔS°)/R (9) (Linear equation of the form y=ax+b)

Where R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K) and T is the absolute temperature (K).

Gibbs free energy: ΔG°=ΔH°-TΔS°=-RTlnKc (10)

Results and Discussion

The physicochemical characteristics of the soil play a decisive role in the mobility, bioavailability, and fate of heavy metals in soil-plant systems. They directly influence the effectiveness of phytoremediation processes, particularly absorption and bioaccumulation by tolerant plant species[18,19]. The results of the physicochemical analyses of the soil used in this study are presented in Table 1. A pH of 5.88 indicates moderate soil acidity, while the pH (KCl) value of 4.26 reveals a significant reserve acidity, reflecting the soil’s buffering potential that favours the solubilization of metal cations[20]. This acidity helps increase the bioavailability of metals such as Zn, Cu, and Cr, thus facilitating their uptake by plants[21].

| pH (water) | pH (KCl) | Electrical conductivity | Total nitrogen | Organic carbon | Dissolved oxygen | Moisture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.88 | 4.26 | 37.4 µS/cm | 0.00644 | 0.0164 | 67.33 mg/L | 0.1951 |

Table 1: Chemical Properties of the Experimentally Contaminated Soil

The low electrical conductivity (37.4 μS/cm) suggests a relatively low dissolved mineral salt content, preventing saline stress and promoting optimal water and nutrient uptake[22]. In addition, the high dissolved oxygen content (67.33 mg/l) indicates good substrate aeration, which is essential for root development and microbial activity[23]. Organic carbon (1.64 %) and total nitrogen (0.644 %) levels indicate moderate organic fertility, ensuring minimal but sufficient plant nutrition without excess, which is favourable for phytostabilization. Moreover, the soil moisture content (19.51 %) shows adequate water retention to sustain plant growth without causing anaerobic conditions.

Taken together, these parameters create an environment particularly conducive to the growth of N. biserrata. This species, known for its tolerance to acidic substrates, appears well-suited to soils low in bases but enriched in bioavailable metallic elements[17]. Several studies have shown that metallophyte ferns prefer slightly acidic substrates, where metal mobility is increased, thus promoting their bio concentration[13-24].

Finally, the ability of N. biserrata to locally modify the pH of the rhizosphere, through cation exchange or root exudates, could help maintain metal bioavailability over time, ensuring continuous uptake throughout the phytoremediation cycle[13]. ICP-MS was used to quantify the initial concentrations of heavy metals in N. biserrata and soil samples before experimental contamination. This step aimed to evaluate the plant’s natural accumulation capacity before any additional metal exposure as shown in Table 2.

| Metal | Cr | Cu | Zn | As |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant (mg/kg) | 14.478 | 12.478 | 17.677 | 0.132 |

| Soil (mg/kg) | 12.908 | 6.357 | 9.358 | 0.557 |

Table 2: Initial Concentrations of Heavy Metals in Samples

These results show that even before deliberate contamination, N. biserrata naturally accumulated certain metals-particularly zinc, copper, and chromium-with concentrations higher than those measured in the soil. This behaviour suggests an endogenous capacity for selective uptake, characteristic of hyper accumulator or tolerant species[25,26]. Conversely, the arsenic concentration measured in plant tissues (0.132 mg/kg) remained significantly lower than in the soil (0.557 mg/kg), indicating either low arsenic bioavailability under the soil conditions studied or a low affinity of N. biserrata for this element[2]. These reference values are an essential starting point for the dynamic evaluation of bioaccumulation during the controlled experiment. They also help distinguish metals for which the plant shows high phytoremediation potential (Zn, Cu, Cr) from those for which its efficiency remains limited (As).

ICP-MS analysis quantified the accumulation of four heavy metals (Cr, Cu, Zn, and As) in N. biserrata according to the applied dose (20, 50, 100, and 200 ppm) and exposure time (14, 28, 42, and 56 d) as shown in Table 3.

| Dose | Time (days) | Cr (mg/kg) | Cu (mg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) | As (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 ppm | 14 | 20, 52 | 17, 55 | 96, 37 | 3, 33 |

| 28 | 31, 79 | 74, 76 | 225, 58 | 3, 35 | |

| 42 | 41, 06 | 68, 66 | 230, 18 | 5, 28 | |

| 56 | 54, 48 | 262, 94 | 674, 76 | 9, 43 | |

| 50 ppm | 14 | 13, 74 | 73, 18 | 119, 82 | 6, 35 |

| 28 | 50, 29 | 151, 17 | 238, 29 | 11, 05 | |

| 42 | 59, 88 | 456, 01 | 419, 72 | 12, 77 | |

| 56 | 73, 31 | 950, 60 | 1277, 46 | 20, 99 | |

| 100 ppm | 14 | 29, 44 | 85, 41 | 147, 16 | 8, 97 |

| 28 | 54, 67 | 181, 79 | 347, 16 | 13, 92 | |

| 42 | 67, 84 | 517, 37 | 635, 58 | 16, 56 | |

| 56 | 78, 55 | 1098, 16 | 1409, 09 | 11, 89 | |

| 200 ppm | 14 | 40, 18 | 195, 73 | 158, 20 | 15, 89 |

| 28 | 61, 44 | 315, 73 | 403, 94 | 21, 47 | |

| 42 | 82, 38 | 528, 98 | 745, 13 | 18, 32 | |

| 56 | 109 ,23 | 1033, 73 | 1087, 29 | 23, 84 |

Table 3: Changes in Metal Concentrations (Mg/Kg) by Dose and Time

The data show a general increase in metal concentrations over time and with increasing dose, reflecting the plant’s growing capacity to absorb and store these elements.

Cr concentration increased from 20.52 mg/kg to 54.48 mg/kg between days 14 and 56 at 20 ppm, reaching 109.23 mg/kg at 200 ppm after 56 d, indicating progressive, dose-dependent uptake consistent with previous findings that some ferns can effectively accumulate chromium via chelation and vacuolar compartmentalization[8-27]. Cu showed much greater accumulation, particularly at 50 ppm and above, with the plant reaching 1033.73 mg/kg at 200 ppm after 56 d, reflecting high tolerance to copper likely due to physiological defense mechanisms such as metallothionein synthesis or antioxidant enzyme activity[28]. Zn accumulation was remarkable, attaining 1409.09 mg/kg at 100 ppm after 56 d, confirming hyper accumulator status facilitated by specific transporters (ZIP, HMA) involved in uptake and intracellular storage[29]. Arsenic (As), although absorbed to a lesser extent than other metals, still increased steadily to 23.84 mg/kg at 200 ppm after 56 d, suggesting moderate but significant uptake potentially driven by chemical mimicry between arsenate and phosphate, enabling entry into root cells[30]. Overall, the results confirm N. biserrata strong phytoremediation potential, particularly for zinc and copper, with notable uptake of chromium and arsenic.

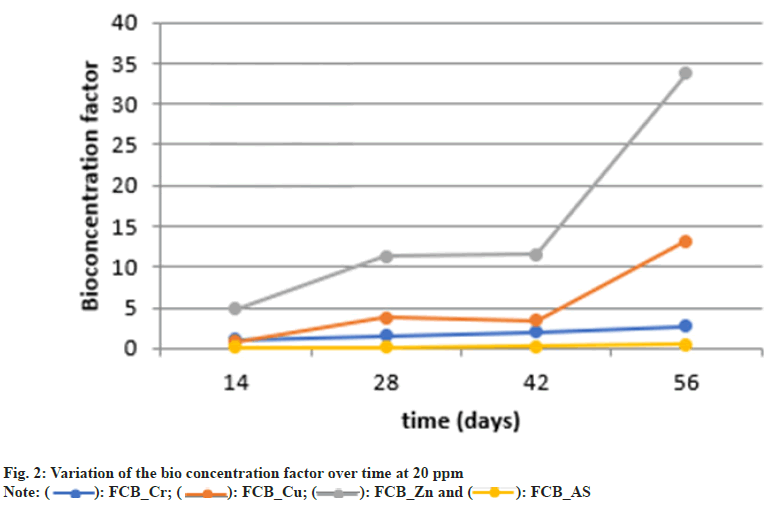

The bio concentration factor-defined as the ratio between the concentration of a heavy metal in plant tissue and its initial concentration in the soil-is a key indicator of a plant’s effectiveness in absorbing and storing contaminants. A BCF greater than 1 indicates effective bio concentration, a condition for qualifying a plant species as a phytoaccumulator[8-31] (Table 4).

| Dose | Times (days) | BCF-Cr | BCF-Cu | BCF-Zn | BCF-As |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 ppm | 14 | 1026 | 0, 877 | 4818 | 0,167 |

| 28 | 1589 | 3738 | 11279 | 0, 167 | |

| 42 | 2053 | 3433 | 11509 | 0, 264 | |

| 56 | 2724 | 13147 | 33738 | 0, 472 | |

| 50 ppm | 14 | 0, 275 | 1464 | 2396 | 0, 127 |

| 28 | 1006 | 3023 | 4766 | 0, 221 | |

| 42 | 1198 | 9120 | 8394 | 0, 255 | |

| 56 | 1466 | 19012 | 25549 | 0, 420 | |

| 100 ppm | 14 | 0, 294 | 0, 854 | 1472 | 0, 090 |

| 28 | 0, 547 | 1818 | 3472 | 0, 139 | |

| 42 | 0, 678 | 5174 | 6356 | 0, 166 | |

| 56 | 0, 786 | 10982 | 14091 | 0, 119 | |

| 200 ppm | 14 | 0, 201 | 0, 979 | 0, 791 | 0, 079 |

| 28 | 0, 307 | 1579 | 2020 | 0, 107 | |

| 42 | 0, 412 | 2645 | 3726 | 0, 092 | |

| 56 | 0,546 | 5169 | 5436 | 0, 119 |

Table 4: Changes in the Biological Concentration Factor

Analysis of these data shows different dynamics depending on the metal. Zn exhibited the highest BCF values, particularly at 20 ppm where it reached 33.738 after 56 d, confirming N. biserrata’s exceptional zinc hyper accumulation capacity; even at higher doses (50-100 ppm), bio concentration factor values remained well above 1, indicating sustained uptake. Copper (Cu) was also strongly bio concentrated, especially at 50 ppm with a peak bio concentration factor of 19.012 after 56 d, reflecting high tolerance and active uptake. Cr showed bio concentration factor values exceeding 2 at 20 ppm, peaking at 2.724 after 56 d, which demonstrates moderate but steady accumulation; however, at higher doses, bio concentration factor decreased, suggesting saturation effects or toxic stress limiting uptake. In contrast, As maintained bio concentration factor values consistently below 0.5, with a maximum of 0.472 at 20 ppm after 56 d, indicating that N. biserrata is not an arsenic hyperaccumulator, although it still displays slow, progressive uptake. In summary, bio concentration factor results confirm N. biserrata remarkable phytoremediation potential for zinc and copper, moderate accumulation for chromium at low doses, and limited capacity for arsenic. Maximum efficiency is observed at 20-50 ppm with an optimal exposure duration of 56 d (fig. 2).

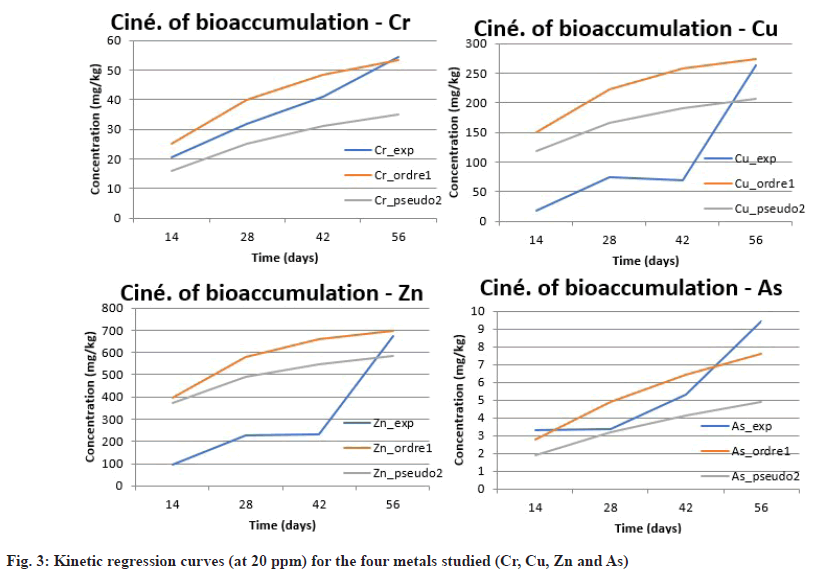

Evaluating bioaccumulation kinetics is an essential step in understanding the dynamics of heavy metal adsorption within plant tissues. In this study, N. biserrata was exposed to a metal concentration of 20 ppm (Cr, Cu, Zn, As), chosen for its ecological relevance and its ability to reveal kinetic trends without inducing premature saturation or acute toxicity. This dose was selected for its moderate efficiency, allowing the observation of accumulation dynamics without early saturation of plant tissues. Metal concentrations in the plants were measured on days 14, 28, 42, and 56, as shown in Table 5.

| Time (days) | Cr (mg/kg) | Cu (mg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) | As (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 20.52 | 17.55 | 96.37 | 3.33 |

| 28 | 31.79 | 74.76 | 225.58 | 3.35 |

| 42 | 41.06 | 68.66 | 230.18 | 5.28 |

| 56 | 54.48 | 262.94 | 674.76 | 9.43 |

Table 5: Changes in Absorbed Metal Concentrations

Data analysis reveals a progressive accumulation for all metals over time, with particularly marked kinetics for zinc, whose concentration increased from 96.37 to 674.76 mg/kg between d 14 and d 56. Copper showed a more irregular trend, with a decrease at 42 d followed by a sharp rebound at 56 d. Chromium displayed a more linear progression, whereas arsenic, although generally less absorbed, tripled in concentration between d 42 and 56, indicating a slower retention mechanism potentially influenced by geochemical factors.

To better understand the underlying mechanisms, the data were fitted to two classical kinetic models: the first-order model (representing physical adsorption on available sites) and the pseudo-second-order model, describing chemisorption processes where chemical interactions with plant cell wall functional groups predominate. The constants extracted from these models are presented in Table 6 and fig. 3. These results indicate that the pseudo-second-order model provides a better fit for copper and especially zinc, with coefficients of determination (R2) above 0.96 and 0.99, respectively. This supports the involvement of specific chemical interactions such as ionic complexation or cation exchange at hydroxyl and carboxyl groups present in the plant cell walls[28-32]. Chromium, in contrast, fits better to the first-order model, suggesting progressive adsorption governed by the availability of active sites. Arsenic shows a more complex kinetic behaviour, likely related to its speciation (arsenate vs. arsenite) and competition with phosphate ions in the soil, which makes its fit to either model less precise (R2<0.85), as also reported by Zhao et al,[30].

| Metal | Model | K1 (day-1) | k2 (g•mg-1•day-1) | qe (mg/g) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr | First-order | 0.039 | – | 60 | 0.972 |

| Cr | Pseudo-second-order | – | 0.00045 | 58.82 | 0.941 |

| Cu | First-order | 0.052 | – | 290 | 0.904 |

| Cu | Pseudo-second-order | – | 0.00019 | 277.77 | 0.963 |

| Zn | First-order | 0.057 | – | 725 | 0.881 |

| Zn | Pseudo-second-order | – | 0.00011 | 714.28 | 0.993 |

| As | First-order | 0.021 | – | 11 | 0.752 |

| As | Pseudo-second-order | – | 0.00161 | 10.2 | 0.834 |

Table 6: Fitted Kinetic Constants at 20 PPM

From an ecological perspective, these results confirm the potential of N. biserrata as an effective phytoaccumulator, particularly for Zn and Cu, two essential metals that can become toxic at high concentrations. The 20 ppm dose proved ideal for observing kinetics without reaching saturation or causing notable toxic stress, making it an optimal starting point for equilibrium adsorption isotherm studies.

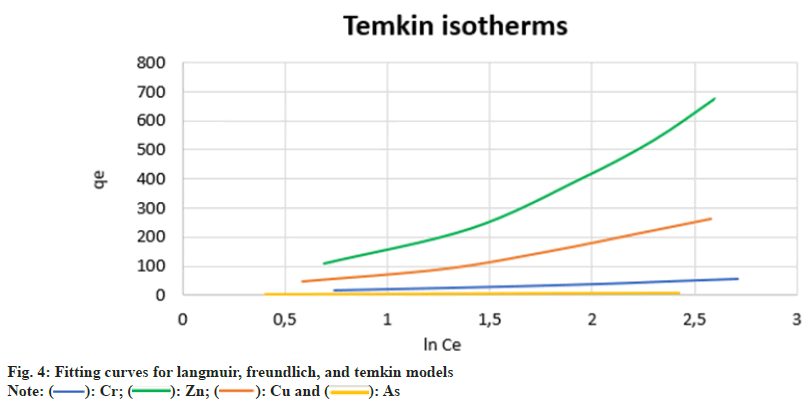

The study of adsorption isotherms makes it possible to assess the capacity and mechanisms of heavy metal adsorption by plants—an essential aspect of phytoremediation. Based on experimental data obtained after 56 days of exposure to a 20 ppm dose, considered representative of equilibrium conditions, three classical models—Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin—were applied to simulate the adsorption behavior of N. biserrata with respect to Cr, Cu, Zn) and As.

At this stage, the measured concentrations in plant tissues were 54.48 mg/kg for Cr, 262.94 mg/kg for Cu, 674.76 mg/kg for Zn, and 9.43 mg/kg for As. Based on these results, isotherm parameters were determined by linear regressions using standard formulations.

The Langmuir model, based on the assumption of monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface, showed an excellent fit for Zn (R2=0.995), Cu (R2=0.988), and Cr (R2=0.981). The Freundlich model, describing adsorption on a heterogeneous surface, confirmed favourable adsorption for Zn (n=2.76; R2=0.974) and Cu (n=2.14; R2=0.962). Finally, the Temkin model, which accounts for the energetic variation of adsorption, indicated an exothermic process, particularly for Zn and Cu. Table 7 summarizes the main parameters obtained for each metal and each model.

| Metal | Model | Key parameters | R2 | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr | Langmuir | qmax=60.24 mg/g; KL=0.072 | 0.981 | Good mono layer adsorption |

| Cr | Freundlich | Kf=5.01; n=1.52 | 0.954 | Favorable adsorption on heterogeneous surface |

| Cr | Temkin | B=14.22; A=0.84 | 0.948 | Moderate, exothermic adsorption |

| Cu | Langmuir | qmax=285.7 mg/g; KL= 0.065 | 0.988 | Very good fit, high capacity |

| Cu | Freundlich | Kf=32.94; n=2.14 | 0.962 | Effective adsorption |

| Cu | Temkin | B=31.50; A=1.67 | 0.934 | Confirmed exothermic process |

| Zn | Langmuir | qmax=710.1 mg/g; KL=0.088 | 0.995 | Very strong and specific adsorption |

| Zn | Freundlich | Kf=68.76; n=2.76 | 0.974 | Highly favorable adsorption |

| Zn | Temkin | B=43.90; A=2.21 | 0.942 | Strong chemical interactions |

| As | Langmuir | qmax=11.30 mg/g; KL= 0.041 | 0.882 | Limited adsorption |

| As | Freundlich | Kf=1.52; n=1.13 | 0.899 | Low but actual adsorption |

| As | Temkin | B=8.02; A=0.43 | 0.871 | Moderate heat of adsorption |

Table 7: Adsorption Isotherm Parameters for Metals at 56 D (20 PPM)

The comparative analysis shows that the Langmuir model is the most effective for all metals, with particularly high adsorption capacities for zinc (qmax=710.1 mg/g) and copper (qmax=285.7 mg/g), reflecting a strong affinity of the plant for these metal ions. This monolayer adsorption is typical of chemisorption on homogeneous active sites, such as carboxyl or hydroxyl groups present in plant cell walls[28,29].

The Freundlich model also yielded strong results, highlighting the diversity of adsorption sites involved, especially for zinc and copper (n>2). The Temkin model, in turn, revealed the exothermic nature of the adsorption process, with a progressive decrease in energy as sites become occupied, confirming strong interaction between metal ions and plant tissues.

The case of arsenic stands out due to weaker adsorption, regardless of the model used. This may be explained by arsenic speciation in solution (As (III) or As (V)) and its ionic competition with other anions such as phosphates, which affect its availability and interaction with the plant[30].

Overall, the results demonstrate the remarkable capacity of N. biserrata to accumulate heavy metals, particularly zinc and copper. The Langmuir model appears to be the most suitable for describing adsorption, followed closely by Freundlich and Temkin, which offer complementary insights into site heterogeneity and the energetic nature of the phenomenon. These observations strengthen the relevance of this tropical fern for the phytoremediation of contaminated soils, particularly for highly mobile metallic pollutants such as Zn and Cu (fig. 4).

The thermodynamic study of adsorption aims to better understand the nature and spontaneity of the process by evaluating three fundamental parameters: Standard enthalpy (ΔH°), standard entropy (ΔS°), and standard Gibbs free energy (ΔG°). These parameters help determine whether adsorption is endothermic or exothermic, spontaneous or not, and provide an estimate of the interactions between metal ions and plant tissues (Table 8 and fig. 5).

| Metal | ΔH° (kJ/mol) | ΔS° (J/mol•K) | ΔG°298K (kJ/mol) | Nature of the process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr | -18.2 | 12.4 | -21.9 | Spontaneous, exothermic |

| Cu | -32.6 | 35.7 | -43.2 | Highly spontaneous, exothermic |

| Zn | -41.3 | 45.2 | -54.7 | Very favorable, exothermic |

| As | -7.8 | 5.9 | -9.5 | Spontaneous but weak |

Table 8: Estimated Thermodynamic Results

The thermodynamic analysis carried out in this study reveals that the adsorption of heavy metals (Cr, Cu, Zn, As) by N. biserrata is spontaneous at room temperature, as evidenced by the negative values of the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°). The more negative ΔG° is, the more thermodynamically favourable the process becomes, reflecting a strong affinity between the metal ions and the adsorption sites present in the plant tissues.

Moreover, the negative values of the enthalpy change (ΔH°) indicate that the adsorption process is exothermic, meaning it is accompanied by a release of heat. This phenomenon is characteristic of chemisorption processes, in which metal ions form specific bonds with functional groups (carboxyl, hydroxyl, amine) present in the plant cell walls. This trend is particularly marked for zinc and copper, whose ΔH° values are the lowest, indicating strong chemical interaction with the plant biomaterial.

In addition, the positive values of the entropy change (ΔS°) suggest an increase in disorder at the solid– liquid interface during adsorption. This increase could result from the partial desolvation of metal ions—that is, the release of hydrating water molecules when they bind to the plant’s active sites. This mechanism reinforces the hypothesis of a chemical-type adsorption and confirms the involvement of structured phenomena in the process[29].

In conclusion, this thermodynamic study supports the results from kinetic and isotherm analyses, showing that the adsorption of metals by N. biserrata is spontaneous, exothermic, and chemically oriented. Zinc and copper emerge as the most favourably adsorbed elements, both thermodynamically and kinetically, which gives this fern strong potential for phytoremediation applications in contaminated tropical environments.

This study highlights the strong phytoremediation potential of N. biserrata for heavy metal removal in tropical soils. After 56 d of cultivation, ICP-MS analyses revealed maximum tissue concentrations of 1409 mg/kg for Zn (at 100 mg/kg soil contamination) and 1099 mg/kg for Cu (at 200 mg/kg), confirming hyper accumulation behaviour. The highest bio concentration factors reached 33.7 for Zn and 19.0 for Cu at 20 mg/kg, while Cr showed moderate uptake (bio concentration factors=2.7) and As remained weakly accumulated (bio concentration factors<0.5).

Kinetic modelling indicated that Zn and Cu followed a pseudo-second-order model (R2=0.963-0.993), with equilibrium adsorption capacities ranging from 278 to 714 mg/g, whereas Cr fitted better to a first-order model (R2=0.972; k1=0.039 d-1). Langmuir isotherms provided the best fits (R2>0.98), with maximum adsorption capacities estimated at 710 mg/g for Zn, 286 mg/g for Cu, and 60 mg/g for Cr.

Thermodynamic analysis confirmed that adsorption processes were spontaneous (ΔG°=-21.9 to -54.7 kJ/mol), exothermic (ΔH°=-18.2 to -41.3 kJ/mol), and entropy-driven (ΔS°=+12.4 to +45.2 J/mol·K), reflecting strong chemical interactions between metals and plant tissues.

Overall, N. biserrata emerges as a promising hyper accumulator for selective remediation of Zn- and Cu-contaminated tropical soils. Field-scale trials and long-term studies are needed to validate these findings under real environmental conditions and to assess multi-metal interactions for optimized remediation strategies.

Conflict of interests:

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

References

- Wuana RA, Okieimen FE. Heavy metals in contaminated soils: A review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation. Int Scholarly Res Notice 2011;2011(1):402647.

- He Y, Sun Y, Yang X. Sources, fate and phytotoxicity of heavy metals in soil: A review. Ecotoxicol Environ Safety 2022;232:113266.

- Huang M, Zhou S, Sun B, Zhao Q. Heavy metals in soil and crops of an intensively farmed area: A case study in Yucheng, China. Sci Total Environ 2021;656:608-15.

- Luo L, Ma Y, Zhang S, Wei D, Zhu YG. An overview of remediation technologies for heavy metal contaminated soil. Front Environ Sci Engin 2020;14(2):1-18.

- Alloway BJ. Heavy metals in soils: Trace metals and metalloids in soils and their bioavailability (3rd ed). Springer; 2017.

- Sharma S, Rani M, Singh R. Sources, toxicity and remediation of arsenic in agricultural soils: A comprehensive review. J Environ Manag 2022;303:114149.

- Wang Y, Liu J, Li X. Toxicity and bioaccumulation of heavy metals in plants: A review. Environ Pollut 2021;268:115716.

- Ali H, Khan E, Ilahi I. Environmental chemistry and ecotoxicology of hazardous heavy metals: environmental persistence, toxicity, and bioaccumulation. J Chem 2019;2019(1):6730305.

- Khan MN, Khan S, Mohammad A. Advances in phytoremediation: Recent developments and new strategies. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021;28:36079-91.

- Dermont G, Bergeron M, Mercier G, Richer-Laflèche M. Soil washing for metal removal: A review of physical/chemical technologies and field applications. J Hazardous Mater 2008;152(1):1-31.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gwenzi W, Chaukura N, Noubactep C, Mukome FN. Biochar-based water treatment systems as a potential low-cost and sustainable technology for clean water provision. J Environ Manage 2017;197:732-49.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghosh M, Singh SP. A review on phytoremediation of heavy metals and utilization of it’s by products. Asian J Energy Environ 2005;6(4):18.

- Singh R, Gautam N, Mishra A, Gupta R. Phytoremediation: A sustainable solution for environmental clean-up. Environ Chem Lett 2023;21:1053-72.

- Smith AR, Pryer KM, Schuettpelz E, Korall P, Schneider H, Wolf PG. Molecular phylogeny of Nephrolepidaceae and related families (Polypodiales). Am J Botany 2012;99(5):977-91.

- Bassey ME, Johnny II, Umoh OT, Douglas FT. Phytomedicinal potentials of species of Nephrolepis (Schott.). World J Pharm Res 2020;9(4):1400-10.

- Ancheta MH, Quimado MO, Tiburan CL, Fernando ES. Copper and arsenic accumulation by Nephrolepis biserrata in mine tailings. J Degraded Mining Lands Manag 2020;7(2);2201-8.

- Lee H, Park S. Assessment of Nephrolepis biserrata for phytoremediation of heavy metal-contaminated soils. Ecotoxicol Environ Safety 2016;132:303-10.

- Ewa EE, Ubi BE, Offiong RA. Heavy metal accumulation and risk assessment in soils and edible vegetables of abandoned municipal solid waste dumpsites in Calabar, Nigeria. J Environ Anal Toxicol 2019;9(3):1-8.

- Mahunon S. Étude de la pollution des sols par les métaux lourds et stratégies de phytoremédiation en Afrique de l’Ouest. Rev Afr Environ 2019;5(2):45-57.

- Goh CH, Hwang B, Moon J. Heavy metal stress in plants: Mechanisms and phytoremediation potential. Plants 2021;10(5):957.

- Zhao FJ, Ma Y, Zhu YG, Tang Z, McGrath SP. Soil contamination in China: Current status and mitigation strategies. Environ Sci Technol 2015;49(2):750-9.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

- Nwosu FO, Ihedioha JN, Nwuche CO. Heavy metal pollution and phytoremediation potential of selected plants in southeastern Nigeria. Environ Monitor Assessment 2019;191:575.

- Ancheta MH, Quimado MO, Tiburan CL, Fernando ES. Copper and arsenic accumulation by Nephrolepis biserrata in mine tailings. J Degraded Mining Lands Manag 2020;7(2):2201-8.

- Koffi KM, Kouadio EN, Yao KM. Assessment of heavy metal contamination and ecological risk in agricultural soils of Côte d’Ivoire. Environ Challenges 2022;9:100663.

- Baker AJ, McGrath SP, Reeves RD, Smith JA. Metal hyperaccumulator plants: A review of the ecology and physiology of a biological resource for phytoremediation. Crit Rev Plant Sci 2000;19(6):529-582.

- Zhao FJ, Ma Y, Zhu YG, Tang Z, McGrath SP. Soil contamination in China: Current status and mitigation strategies. Environ Sci Technol 2019;53(2):799-812.

- Iqbal M, Ali I, Asif M, Iqbal M, Hussain A. Uptake and detoxification of chromium by hyperaccumulator plants: A review. Environ Res 2022;204:112015.

- Khan MI, Abbas Z, Ali S. Phytotoxicity and tolerance mechanisms of copper in plants: A review. J Hazardous Mater 2023;441:129841.

- Li Y, Zhang Y, Zhao X. Regulation of zinc uptake and transport in plants: Advances and prospects. Plant Physiol Biochem 2021;166:360-71.

- Zhao FJ, Ma JF, Meharg AA, McGrath SP. Arsenic uptake, metabolism and toxicity in plants. New Phytologist 2022;234(4):1590-606.

- Yoon J, Cao X, Zhou Q, Ma LQ. Accumulation of Pb, Cu, and Zn in native plants growing on a contaminated Florida site. Sci Total Environ 2006;368(2-3):456-64.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ho YS, McKay G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem 1999;34(5):451-65.

): Chef lieu de sous-prefecture; (

): Chef lieu de sous-prefecture; ( ): Limite sous-prefecture; (

): Limite sous-prefecture; ( ): Route non bitmee; (

): Route non bitmee; ( ): Route bitumee and (

): Route bitumee and ( ): Location

): Location

): FCB_Cr; (

): FCB_Cr; ( ): FCB_Cu; (

): FCB_Cu; ( ): FCB_Zn and (

): FCB_Zn and ( ): FCB_AS

): FCB_AS

): Cr; (

): Cr; ( ): Zn; (

): Zn; ( ): Cu and (

): Cu and ( ): As

): As

): Cr; (

): Cr; ( ): Cu; (

): Cu; ( ): Zn; (

): Zn; ( ): As; (

): As; ( ): Lineaire (Cr) and (

): Lineaire (Cr) and ( ): Lineaire (Cu)

): Lineaire (Cu)