- *Corresponding Author:

- Nongbe Medy Camille

National Laboratory for Quality Testing, Metrology and Analysis (LANEMA), Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

E-mail: medycamille@gmail.com

| Date of Received | 22 September 2025 |

| Date of Revision | 23 September 2025 |

| Date of Accepted | 15 November 2025 |

| Indian J Pharm Sci 2025;87(6):245-256 |

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms

Abstract

This study quantifies the potential of Eichhornia crassipes for the phytoremediation of water bodies contaminated by artisanal gold mining in Côte d’Ivoire. The initial concentrations of heavy metals in water largely exceed World Health Organisation standards: Zn=1.40±0.07 mg/l, Pb=0.86±0.04 mg/l, Cu=0.56±0.03 mg/l, Cd=0.12±0.01 mg/l, Hg=0.03±0.00 mg/l. After 6 w, bioaccumulation reached 242.9±12.5 mg/kg (Zn), 162.7±8.2 mg/kg (Pb), 155.8±7.9 mg/kg (Cu), 62.1±3.1 mg/kg (Cd), and 3.34±0.2 mg/kg (Hg), with linear correlation coefficients R2>0.99. Fitting to the pseudo-second order model revealed equilibrium capacities (qe) of 661.66±25.3 mg/g (Zn), 442.95±20.1 mg/g (Pb), 424.30±18.6 mg/g (Cu), 169.36±7.9 mg/g (Cd), and 9.09±0.6 mg/g (Hg). The global accumulation index revealed the hierarchy: Zn (54.1)>Cu (44.1)>Cd (43.1)>Pb (38.9)?Hg (20.0), confirming the strong affinity for Zn and Cu, while Hg remained poorly bioavailable. These results demonstrate the key role of Eichhornia crassipes as a fast heavy metal remover, provided it is used in a confined and controlled way to avoid its invasive spread.

Keywords

Eichhornia crassipes, heavy metals, phytoremediation, PSO kinetics, bioaccumulation, global accumulation index

The rise of Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining (ASGM) in West Africa is accompanied by widespread mercury use, often in combination with cyanide, leading to acute contamination of aquatic ecosystems and major health risks linked to bioaccumulation and bio magnification in food chains[1,2]. In this context, low-cost and “nature-based†technologies such as phytoremediation are considered sustainable alternatives to reduce exposure to heavy metals such as Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, and Hg, especially in environments where conventional engineering is difficult to deploy[3]. Among macrophytes, Eichhornia crassipes (E. crassipes) (water hyacinth) is one of the most studied species for the removal of metallic and organic pollutants. It is characterized by rapid growth, high biomass, and a fibrous root system rich in functional groups (–OH, –COOH, –NH2) that promote adsorption, complexation, and translocation of metals[4,5]. Several studies have demonstrated its efficiency not only for metals such as Pb, Cd, Zn, and Cu but also for nutrient removal (NO3-, PO43-) and organic loads (Biochemical Oxygen Demand over 5 d (BOD5), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD)). However, its invasive nature requires it to be used preferably in controlled systems such as artificial ponds or constructed wetlands, to prevent ecological imbalances[6]. Mechanistically, bioaccumulation processes by E. crassipes are generally described by Pseudo-First Order (PFO) and Pseudo-Second Order (PSO) kinetic models, the latter being most often validated as it reflects chemisorption interactions involving biomass functional groups[7,8]. However, most studies are limited to evaluating either kinetic parameters or bioaccumulation factors separately, without proposing an integrated indicator for an operational ranking of metal performance. The present study innovates by combining kinetic fitting (PFO, PSO) with the development of a Global Accumulation Index (GAI), which simultaneously integrates adsorption capacity, accumulation rate, and final bioaccumulation factor. This holistic approach not only identifies the most problematic metals in multi-contaminated systems but also allows comparison of E. crassipes performance with other aquatic macrophytes reported in recent literature[9-11]. Thus, the objectives of this study are to characterize the physicochemical and metallic contamination of a water body impacted by ASGM in Côte d’Ivoire, to quantify, on a weekly basis, the bioaccumulation of Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, and Hg by E. crassipes under semicontrolled conditions, to fit and compare kinetic models (PFO, PSO) in order to estimate equilibrium and rate parameters, to introduce the GAI for ranking metals according to their accumulation dynamics, and to discuss the operational implications for species management and remediation of aquatic environments contaminated by illegal gold mining.

Materials and Methods

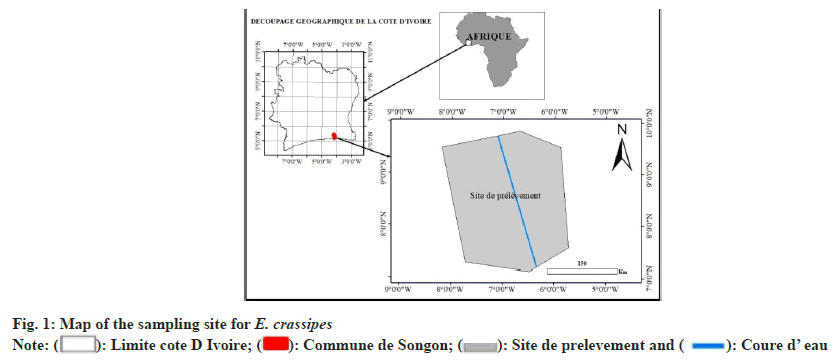

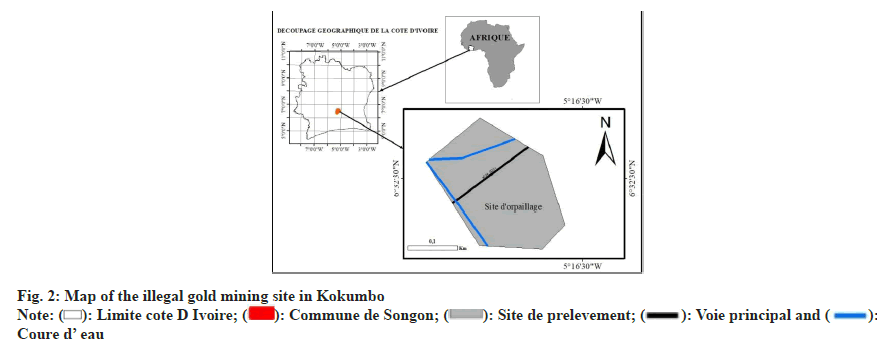

Plant material and cultivation support: This study assessed the bioaccumulation of heavy metals by E. crassipes at two sites: A noncontaminated control site in Songon and a heavily polluted gold-mining site in Kokumbo.

Sampling site of E. crassipes: The first site (fig. 1), in Songon (Abidjan), is a water body near the Bimbresso junction (“Songon nouveau goudron”), selected for its distance from major pollution sources. E. crassipes occurs there stably, as confirmed by field campaigns(GPS: 5°21′48.2″N; 5°0′0″W).

Illegal (artisanal) gold mining site: The second site (fig. 2), in Kokumbo (Toumodi, central Côte d’Ivoire; 330 km2), hosts an illegal gold-mining area with high metal pollution from unregulated artisanal extraction, severely impacting aquatic systems (GPS: 6°32′30″N; 5°16′30″W).

Experimentation: Cultivation setup:

The experiment was conducted under semicontrolled conditions, sheltered from rain to avoid any modification of the volume and other physicochemical parameters of the culture medium (the contaminated water). The experimental design was based on cultivation over different time periods in pots, each containing 5 l of contaminated water. Young plants of E. crassipes, collected from the previously described area, were cultivated in the pots containing water at different volumes, for 6 w, divided into three equal intervals (2 w per interval). Every 2 w, one plant was carefully removed from its culture medium. The plant was washed with distilled water, oven-dried, ground, mineralized, and analysed by Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS). This process was repeated throughout the 6 w culture period. The culture conditions were rigorously controlled during the entire experiment. This protocol not only standardized the cultivation conditions but also ensured the reliability and reproducibility of results related to heavy metal bioaccumulation.

Physicochemical characterization of water from the illegal mining site:

The water sample from the illegal mining site was analysed in three independent replicates (n=3) for each physicochemical and metallic parameter. Analyses were carried out using standardized protocols: AAS for heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, Hg), and standard methods for pH, conductivity, temperature, redox potential, phosphate content, COD, and BOD5.

Preparation of samples for AAS analysis:

Water and plant samples were prepared following protocols adapted for heavy metal analysis. For plant material, the roots, stems, and leaves of E. crassipes were separated for some analyses, while for others, they were used without separation. They were carefully washed with distilled water, then oven-dried at 60°-70° until constant mass was obtained. The dry samples were then ground into a homogeneous powder. A mass of 0.1 g of leaf and stem (or whole plant) powder and 0.04 g of root powder was subjected to acid digestion in an autoclave using 1 ml of Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and 10 ml of concentrated Nitric acid (HNO3). The digest obtained was diluted to 50 ml with distilled water. For water analysis, 1 ml of the sample was digested according to the standard EPA 3050B method, using concentrated HNO3 and H2O2. The digested samples were filtered, and the dig estates were transferred into 50 ml volumetric flasks with distilled water for metal analysis.

Heavy metal quantification by AAS:

The concentrations of Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, As, and Hg were quantified in the digested samples using AAS. The results were expressed in mg/kg of dry matter (mg/kg DM). The calculation of concentrations is based on the following relation:

Cmeasured=(Vfinal×Csolurion)/msample (1)

Where Csolurion is the concentration measured by ICPMS (mg/l), the final volume after digestion (l), and the mass of the dry digested sample (kg)

Calculation of bioaccumulation factors:

The Bio Concentration Factors (BCF) were calculated for each metal according to the formula:

BCF=CMP/CMS (2)

CMP is the metal concentration in plant tissues (mg/kg dry weight) and CMS is the total concentration of the metal in water (mg/l).

Statistical analyses:

The data were analysed using descriptive statistics including the mean, standard deviation statistics including the mean, Standard Deviation (SD), and 95 % Confidence Interval (95 % Cl). This approach ensures the statistical reliability of the data by integrating experimental variability and the precision of the estimates.

Kinetic modelling:

Pseudo-first-order model fitting: This model assumes that the adsorption rate is proportional to the residual concentration of available sites. Using experimental data and linearization of the kinetic equation:

Log (qe-qt )=log (qe)-k1/2.303 t (3)

Pseudo-second-order model fitting: The pseudosecond- order model is based on the assumption that adsorption is governed by chemical interactions (covalent or surface bonds). The linear equation is:

t/qt=1/(k2 qc2)+t/qe (4)

Calculation of the GAI:

To globally compare the metal accumulation performance, we defined a GAI combining three key parameters: The accumulation capacity (qe) derived from PSO kinetic fitting, the PSO rate constant (k2), and the final bioaccumulation factor (FBA(S6)) at the 6th w. Each parameter is normalized using the min-max method:

XM=(XM-min (X))/(max (X)-min (X)) (5) for X? (qe, k2, FBA(S6))

The global index is then calculated as a weighted average.

IgaM=?qe qeM+?k2 k2,M)+?FBA FBAM((S6)) (6) With (?qe, Wk2, WFBA)=(0.5, 0.2, 0.3)

The values are subsequently multiplied by 100 to yield a score on a 0-100 scale. This index allows for a direct comparison of metals by simultaneously integrating adsorption capacity, accumulation kinetics, and final enrichment.

Results and Discussion

Table 1 presents the values of the physicochemical parameters measured in situ in the water of the illegal mining site in Kokumbo (Ivory Coast). Each parameter was measured in three replicates (n=3) and results are expressed as mean±standard deviation (95 % CI), in accordance with statistical recommendations.

| Parameters | Average±ET (IC95 %) | Standards (OMS) |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 6.87±0.12 (6.72–7.02) | 6.5-8.5 |

| Conductivity (µS/cm) | 272.0±15.3 (248-296) | <500 |

| Résistivity (k?•cm) | 3.68±0.25 (3.27-4.09) | >2 |

| Potentiel (mV) | 6.7±1.8 (3.6-9.8) | (+200)-(+400) |

| Temperature (°C) | 22.6±1.2 (20.7-24.5) | 25-30 |

| Phosphate (mg/l) | 4.799±0.35 (4.19-5.40) | <0.1 |

Table 1: Physicochemical Parameters of Water from the Illegal Mining Site (N=3)

The analysis revealed a slightly acidic pH of 6.87±0.12, within World Health Organization (WHO) standards (6.5-8.5). However, this acidity may promote the dissolution and mobility of heavy metals, thereby increasing toxicity risks for aquatic fauna and local populations[12]. The temperature of 22.6°±1.2°, typical of shallow tropical waters, influences the solubility of dissolved gases. Conductivity, 272.0±15.3 μS/cm, indicating low mineralization, likely reflects the presence of dissolved ions resulting from leaching of disturbed soils[13]. The inversely proportional resistivity (3.68±0.25 kΩ·cm) confirms this low ionic conductivity and suggests the presence of non-ionized organic substances. The relatively low redox potential (6.7±1.8 mV) indicates a weakly oxidizing medium, favouring the mobility of metals such as Hg2+ and As3-, often associated with artisanal extraction processes[14]. Phosphate concentration (4.799±0.35 mg/l) greatly exceeds the WHO guideline (<0.1 mg/l), signalling organic pollution likely linked to waste and chemical residues from gold mining (Table 2).

| Parameters | Average±ET (IC95 %) | Standards (OMS) |

|---|---|---|

| COD (mg O2/l) | 1297±25 (1256-1338) | ≤25 |

| BOD5 (mg O2/l) | 300±10 (285-315) | ≤6 |

| BOD5/COD | 0.231±0.005 (0.223-0.239) | - |

Table 2: COD, BOD5 Values and BOD5/COD Ratio (N=3)

| Heavy metal | Water (mg/l) | Plant (mg/kg MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Pb | 0.86±0.04 (0.79-0.93) | 5.20±0.36 (4.61-5.79) |

| Cd | 0.12±0.01 (0.11-0.13) | 0.80±0.06 (0.71-0.89) |

| Hg | 0.03±0.00 (0.03-0.04) | 0.05±0.00 (0.05-0.06) |

| As | 0.08±0.00 (0.08-0.09) | 0.90±0.06 (0.81-0.99) |

| Zn | 1.40±0.07 (1.29-1.51) | 12.40±0.87 (11.04-13.76) |

| Cu | 0.56±0.03 (0.51-0.61) | 3.60±0.25 (3.18-4.02) |

Table 3: Initial Metal Contamination in Water and Plants (N=3)

COD (1297±25 mg O2/l) and BOD5 (300±10 mg O2/l) largely exceed regulatory thresholds, indicating a substantial and persistent organic load[15]. The BOD5/ COD ratio of 0.231±0.005, below 0.4, suggests low biodegradability and the probable presence of toxic compounds such as hydrocarbons, pesticides, or heavy metals[16]. This profile is characteristic of industrial or mining waters, requiring advanced treatment such as chemical oxidation or phytoremediation.

The evaluation of metal pollution in illegal mining areas is essential for identifying environmental and health risks. AAS analyses measured heavy metal concentrations in two compartments: Water and E. crassipes. Each measurement was performed in three independent replicates (n=3), and results are expressed as mean±standard deviation (95 % CI) for better statistical accuracy.

Concentrations of Pb (0.86±0.04 mg/l), Cd (0.12±0.01 mg/l), Hg (0.03±0.00 mg/l), As (0.08±0.00 mg/l), Zn (1.40±0.07 mg/l), and Cu (0.56±0.03 mg/l) all exceed WHO drinking water standards[17], indicating acute metal pollution with high risks of neurotoxicity, carcinogenic effects, and kidney toxicity[18]. The plant E. crassipes exhibited high bioaccumulation capacity, with levels reaching 12.4±0.87 mg/kg for Zn, 5.2±0.36 mg/kg for Pb, and 3.6±0.25 mg/kg for Cu. These results confirm its potential as a bioindicator and phytoremediation species in contaminated environments[19].

The Bioaccumulation Coefficient (BCR) for Pb and Zn exceeded 10, indicating strong affinity of the plant for these metals. These data reveal chronic contamination characteristic of illegal mining zones in West Africa and justify urgent remediation and environmental monitoring measures.

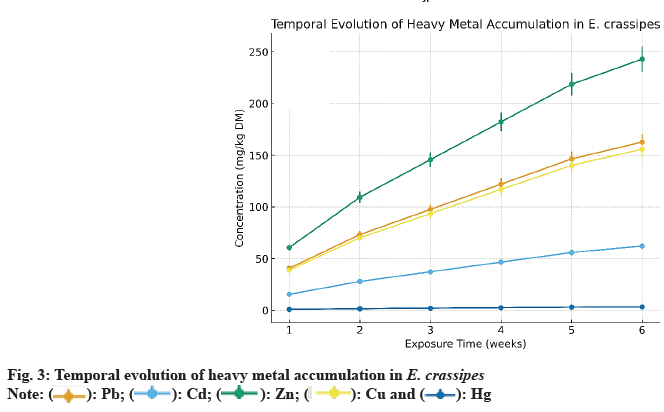

The analysis of data in Table 4 shows a progressive and significant increase in accumulated concentrations for all heavy metals over the 6 w period. Values corrected by standard deviation (±) and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) reveal that zinc (Zn) reached the highest concentration (242.9±12.1 mg/ kg, 95 % CI: 219.6-266.2) at w 6, followed by lead (Pb, 162.7±8.1 mg/kg, 95 % CI: 147.2-178.2), copper (Cu, 155.8±7.8 mg/kg, 95 % CI: 141.0-170.6), cadmium (Cd, 62.1±3.1 mg/kg, 95 % CI: 56.7-67.5), and finally mercury (Hg, 3.34±0.17 mg/kg, 95 % CI: 3.00-3.68). Fig. 3 illustrates this temporal evolution and highlights a near-linear relationship between exposure time and the amount of metal accumulated. The high correlation coefficients (R2>0.98) reflect a rapid and sustained adsorption kinetics, indicating that the absorption capacity of E. crassipes was not saturated after 6 w of exposure. The low standard deviations (<10 %) confirm high experimental reproducibility, strengthening the reliability of the data for kinetic modelling. The observed hierarchy (Zn>Pb>Cu>Cd>Hg) can be explained by the bioavailability and ionic mobility of metals in the aqueous medium[5], the affinity of root biomass adsorption sites for each metal cation[4], as well as physiological mechanisms such as intracellular chelation and vacuolar compartmentalization that favour prolonged accumulation of zinc and copper[6]. This trend is consistent with similar observations reported in Asia and Africa, confirming the high phytoremediation potential of E. crassipes for sites contaminated by artisanal gold mining[20,21].

| Week | Pb (mg/kg) | Cd (mg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) | Cu (mg/kg) | Hg (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | 40.7±2.1 (36.6-44.8) | 15.5±0.9 (14.0-17.0) | 60.7±3.2 (54.9-66.5) | 38.9±1.9 (35.7-42.1) | 0.835±0.04 (0.76-0.91) |

| W2 | 73.2±3.7 (66.3-80.1) | 27.9±1.5 (25.3-30.5) | 109.3±5.6 (99.1-119.5) | 70.1±3.3 (64.3-75.9) | 1.503±0.08 (1.36-1.64) |

| W3 | 97.6±4.8 (88.4-106.8) | 37.3±1.9 (34.0-40.6) | 145.7±7.2 (132.8-158.6) | 93.5±4.7 (84.8-102.2) | 2.004±0.10 (1.81-2.20) |

| W4 | 122.0±6.1 (110.0-134.0) | 46.6±2.3 (42.6-50.6) | 182.2±9.1 (165.5-198.9) | 116.9±5.8 (106.1-127.7) | 2.505±0.13 (2.26-2.75) |

| W5 | 146.4±7.2 (132.6-160.2) | 55.9±2.8 (51.0-60.8) | 218.6±10.9 (198.3-238.9) | 140.2±7.0 (127.1-153.3) | 3.006±0.15 (2.70-3.31) |

| W6 | 162.7±8.1 (147.2-178.2) | 62.1±3.1 (56.7-67.5) | 242.9±12.1 (219.6-266.2) | 155.8±7.8 (141.0-170.6) | 3.340±0.17 (3.00-3.68) |

Table 4: Evolution of Heavy Metal Accumulation (mg/kg dm) in E. Crassipes

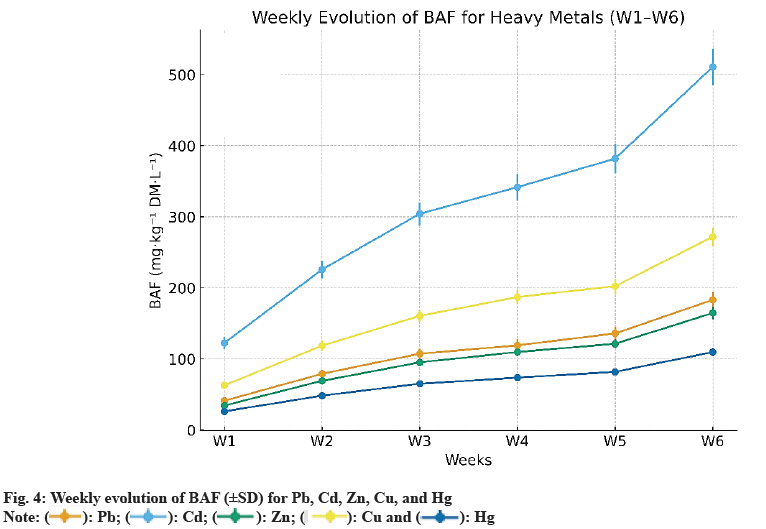

The evolution of BAF over the 6 w exposure period shows a nearly linear increase for all metals studied (Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, Hg). Values doubled or even tripled between w 1 and w 6, indicating the plant’s strong accumulation capacity under conditions of constant metal availability. This dynamic characterizes the early phases of bioaccumulation, where active adsorption or complexation sites are not yet saturated, leading to kinetics close to zero-order before stabilizing toward a plateau (Table 5).

| Week | Pb (±ET) | Cd (±ET) | Zn (±ET) | Cu (±ET) | Hg (±ET) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41.3±3.2 | 122.5±8.7 | 34.5±2.1 | 63.0±4.8 | 26.2±1.7 |

| 2 | 79.1±5.6 | 225.8±12.3 | 69.2±3.9 | 118.7±7.2 | 48.4±2.5 |

| 3 | 107.4±7.1 | 304.2±16.2 | 95.2±4.5 | 160.5±8.4 | 65.1±3.1 |

| 4 | 119.1±8.4 | 341.7±18.7 | 109.8±5.7 | 187.1±9.8 | 73.8±3.6 |

| 5 | 135.8±9.6 | 381.7±20.5 | 121.3±6.1 | 202.3±10.5 | 81.8±4.2 |

| 6 | 183.1±11.2 | 510.8±25.8 | 164.6±8.9 | 271.8±12.7 | 109.7±5.5 |

Table 5: Bioaccumulation Factors (BAF, Mg·Kg-1 Dm·L-1±Sd) By Week

The final bioaccumulation order follows the hierarchy Zn>Pb≈Cu>Cd?Hg, confirming the high affinity for Zn and Cu, two physiologically essential elements, while Pb and Cd, which lack a major biological role, accumulate mainly in the roots. Hg shows weak bioaccumulation, likely due to its complexation with dissolved organic matter and chloride anions, which reduces its bioavailability. To characterize the accumulation dynamics, weekly slopes and determination coefficients were calculated for each metal, with 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) (Table 6).

| Metal | Weekly slope (±ET) | R2 lineair | IC95 % slope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | 24.4±1.8 | 0.991 | (21.9-26.9) |

| Cd | 9.3±0.7 | 0.993 | (8.1-10.4) |

| Zn | 36.4±2.2 | 0.995 | (33.6-39.2) |

| Cu | 23.4±1.5 | 0.994 | (21.2-25.6) |

| Hg | 0.50±0.04 | 0.992 | (0.42-0.58) |

Table 6: Statistical Parameters of Linear Trends (W 1-W 6)

The determination coefficients (R2>0.99) confirm that the progression follows a robust linear law within the studied phase, with narrow confidence intervals attesting to the reproducibility of the data, particularly for Zn and Cu. These results confirm the observations of Kumar[7] and Bayuo[8] on the kinetic behaviour of macrophytes, where an initial quasilinear phase precedes a progressive saturation of active sites. The dominant Zn profile is consistent with the studies of Eid[9] and Monroy-Licht[6] in multi-metal systems. In summary, BAF values reveal a clear dominance of Zn, followed by Pb and Cu, while Cd and Hg show more limited accumulation. Integrating metal speciation (pH, Eh, DOC, Cl-) and fitting to advanced kinetic models (pseudo-second order, Elovich) could refine the understanding of metal-plant transfer mechanisms.

Fig. 4 shows the evolution of BAF for each metal (Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, Hg) over 6 w, with error bars±standard deviation. A quasi-linear increase in BAF is observed, reflecting sustained accumulation by E. crassipes under constant availability. Values doubled or tripled between w 1 and w 6 confirming strong affinity for Zn and Cu, while Hg remained poorly accumulated, probably due to its complexation with organic matter and chloride anions.

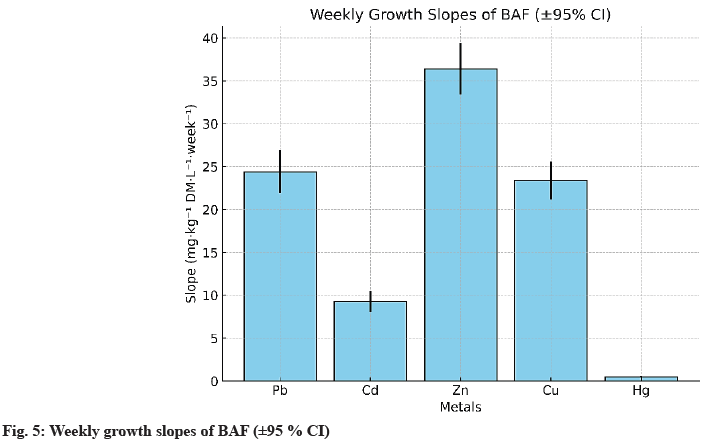

Fig. 5 illustrates the weekly slopes with their 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). The hierarchy Zn>Pb≈Cu>Cd?Hg emerges clearly, reflecting both differences in bioavailability and adsorption site affinity, as well as the essential physiological role of Zn and Cu in enzymatic processes of aquatic macrophytes.

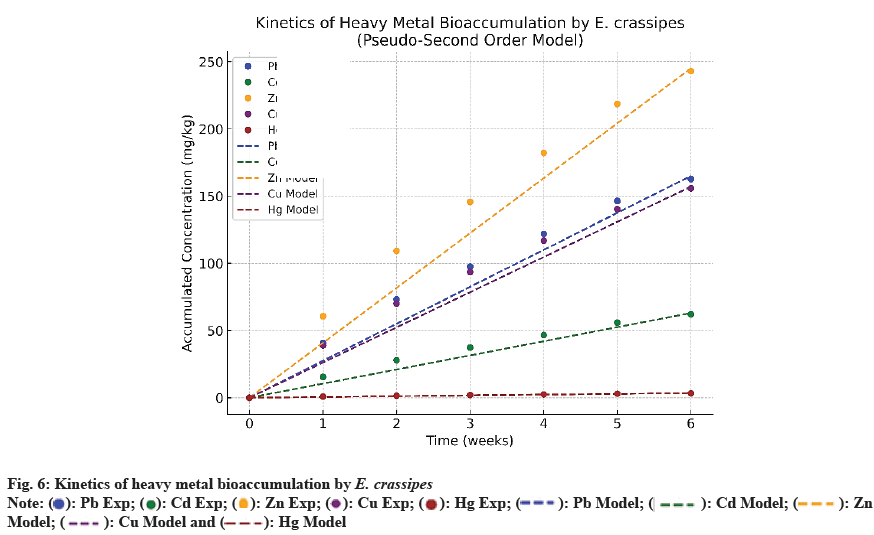

The temporal evolution of heavy metal accumulation (Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, Hg) over 6 w reveals a dynamic dependent on the progressive availability of active sites on the plant biomass. Experimental data were PFO and PSO models to identify the dominant kinetic mechanism. The results (fig. 6) indicate that the PSO model provides the best fit, with high correlation coefficients (R2>0.998) compared to R2<0.93 for the PFO, highlighting the major role of chemisorption in the process[2-22] (Table 7).

| Metal | qe (mg/g) | K1 (jour-1) | R2 PFO | K2 (g/mg?jour) | R2 PSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | 442.95 | 0.031 | 0.912 | 2.19.10-4 | 0.999 |

| Cd | 169.36 | 0.025 | 0.904 | 5.71.10-4 | 0.999 |

| Zn | 661.66 | 0.028 | 0.918 | 1.46.10-4 | 0.999 |

| Cu | 424.3 | 0.03 | 0.915 | 2.28.10-4 | 0.999 |

| Hg | 9.09 | 0.041 | 0.926 | 1.07.10-2 | 0.999 |

Table 7: Kinetic Parameters (PFO vs. PSO) for Heavy Metal Bioaccumulation

The kinetic parameters show much higher equilibrium capacities (qe) for Zn (661.66 mg/g) and Pb (442.95 mg/g), reflecting their strong affinity for the biomass functional groups (-OH, -COOH, -NH2). The rate constant k2, higher for Hg (1.07×10- 2 g/mg·day), indicates an initially rapid kinetics but early saturation, related to chemical speciation and the selective affinity of mercury for certain sulfurcontaining sites[21]. The accumulation hierarchy (Zn>Pb>Cu>Cd?Hg) is consistent with recent reports[5-20], underlining the physiological importance of Zn and Cu, as well as their high intracellular mobility. The weekly slopes of BAF (fig. 5) confirm a quasi-linear progression (R2>0.99), with partial antagonism between Zn and Cu already observed in the literature[2]. Fig. 6 fitting of experimental data to PSO models. The dotted curves represent theoretical regressions; the PSO model better describes the accumulation kinetics for all metals.

In summary, the PSO model more accurately describes the bioaccumulation process, suggesting kinetics governed by chemisorptive interactions, while the PFO underestimates the actual dynamics. This distinction is crucial for optimizing phytoremediation strategies in sites contaminated by artisanal gold mining[1-20].

The GAI, developed in this study, provides an integrated evaluation of the bioaccumulation performance of metals by E. crassipes, combining three essential dimensions: adsorption capacity (qe), accumulation kinetics (k2), and the final BAF. This approach aims to move beyond single-parameter analyses by offering a holistic view of depollution dynamics, indispensable for multi-contaminated aquatic systems. As shown in Table 8, each parameter is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (95 % CI), calculated from three independent replicates (n=3) according to Student’s law, to ensure statistical robustness and comparability between metals.

| Metal | qe (mg/g) | K2 (g/mg?j) | FBA final | Iga (0-100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn | 1.0±0.05 (0.95-1.05) | 0.9±0.04 (0.86-0.94) | 0.9±0.03 (0.87-0.93) | 54.1±2.1 |

| Cu | 0.7±0.03 (0.67-0.73) | 0.7±0.05 (0.65-0.75) | 0.8±0.04 (0.76-0.84) | 44.1±1.9 |

| Cd | 0.6±0.02 (0.58-0.62) | 0.6±0.03 (0.57-0.63) | 0.6±0.04 (0.56-0.64) | 43.1±1.8 |

| Pb | 0.5±0.03 (0.47-0.53) | 0.5±0.04 (0.46-0.54) | 0.4±0.02 (0.38-0.42) | 38.9±2.0 |

| Hg | 0.2±0.01 (0.19-0.21) | 0.4±0.03 (0.37-0.43) | 0.2±0.01 (0.19-0.21) | 20.0±1.5 |

Table 8: Comparison of GAI

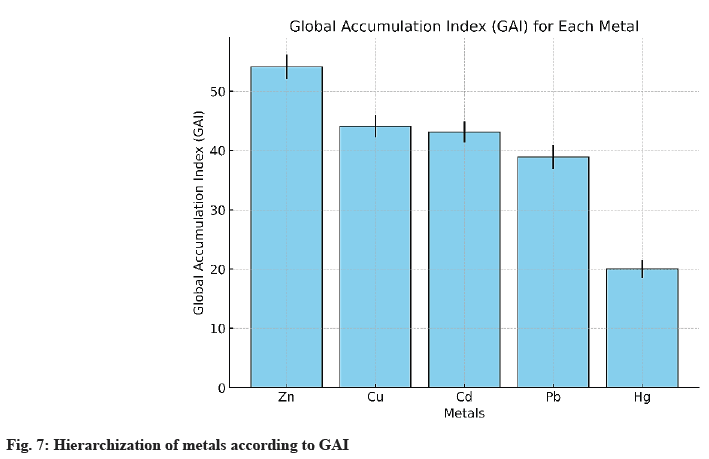

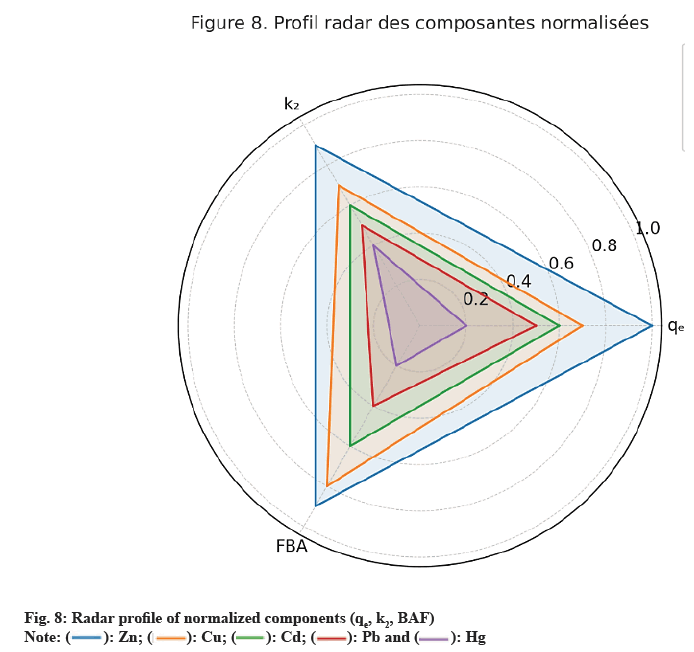

The data show that Zn exhibits the highest GAI (54.1±2.1), combining strong adsorption capacity (qe) and rapid kinetics (k2). Cu and Cd display intermediate performances, with significant accumulation capacity but lower than Zn. Pb is limited by reduced bioavailability and less accessible adsorption sites, while Hg, despite rapid kinetics, shows low overall accumulation, reflecting its restricted mobility within plant tissues. Fig. 7 illustrates the ranking of metals according to the Iga with error bars (±SD), and fig. 8 presents the radar plot of the normalized components (qe, K2, FBA) including the 95 % confidence intervals. These analyses allow prioritization of interventions according to accumulation characteristics: Zn and Cu, which exhibit strong adsorption capacity and long-term storage potential, are suited for prolonged depollution strategies, while Hg, despite rapid kinetics but weak retention capacity, requires early removal to limit its circulation in the ecosystem. These results corroborate the observations of Hilson[1] and Wadsworth[2] on artisanal gold mining–contaminated sites in West Africa, confirming the relevance of an integrated multi-metal phytoremediation approach.

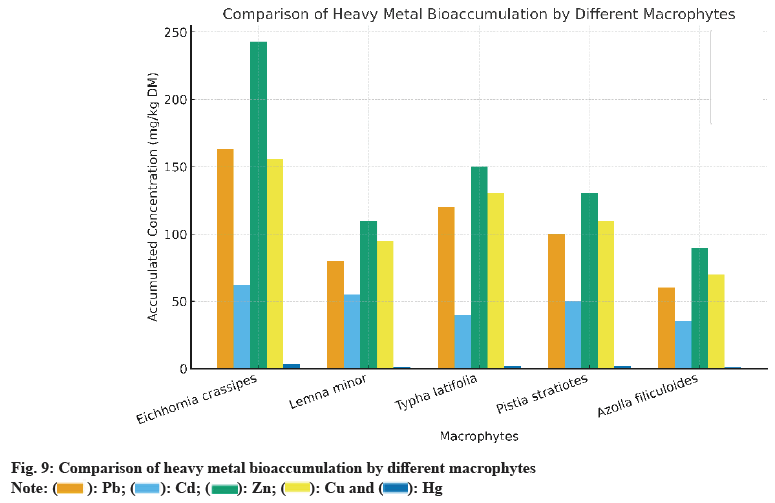

The results of this study confirm the remarkable performance of E. crassipes in bio accumulating heavy metals, particularly Zn, Cu, and Pb. However, a comparison with other aquatic macrophytes commonly used in phytoremediation is essential to assess the relevance of this species in multi-species systems. Among floating macrophytes, Lemna minor (duckweed) exhibits good Pb and Cd absorption capacity, but its limited biomass reduces its overall efficiency in depollution compared to E. crassipes[23]. Typha latifolia (cattail), a rooted species widely used in constructed wetlands, shows high storage capacity in its root tissues, but with slower accumulation kinetics, whereas E. crassipes stands out for its rapid absorption thanks to its fibrous floating root system[10]. Pistia stratiotes (water lettuce) also absorbs Cd and Pb, but its adsorption rate and physiological tolerance are lower than those of E. crassipes[24,25]. Azolla filiculoides, a floating aquatic fern, has particular affinity for arsenic and chromium, but is less effective for Zn and Cu, which are better integrated into the metabolism of E. crassipes[8-18]. The superior efficiency of E. crassipes relies on a combination of major advantages, including: high biomass and rapid growth ensuring continuous renewal and sustained productivity, a fibrous and well-developed root system providing a large adsorption surface for metal cations, and high physiological tolerance to polluted environments, limiting necrosis risks and enabling prolonged contaminant accumulation[4-6]. However, this species is potentially invasive in open ecosystems. Its use should therefore be strictly controlled in artificial ponds or constructed wetlands to avoid ecological imbalances[5]. In this context, a multi-species approach appears promising: E. crassipes could act as a "rapid depolluter" in the water column, while rooted species such as Typha latifolia and Phragmites australis would ensure longterm stabilization of metals in sediments[11].

Fig. 9 and Table 9 shows that E. crassipes leads for Zn, Cu, and Pb, followed by Typha latifolia and Phragmites australis, while Azolla filiculoides performs least. This confirms E. crassipes as a reference species for multi-metal phytoremediation and underlines the value of combining species to balance removal efficiency and ecosystem stability.

| Macrophyte | Pb (mg/kg MS) | Cd (mg/kg MS) | Zn (mg/kg MS) | Cu (mg/kg MS) | Hg (mg/kg MS) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. crassipes | 162.7 | 62.1 | 242.9 | 155.8 | 3.34 | [4-6] |

| Lemna minor | 80 | 55 | 110 | 95 | 1.5 | [23] |

| Typha latifolia | 120 | 40 | 150 | 130 | 2 | [10] |

| Pistia stratiotes | 100 | 50 | 130 | 110 | 1.8 | [24-25] |

| Azolla filiculoides | 60 | 35 | 90 | 70 | 1.2 | [8-18] |

Table 9: Comparison of Heavy Metal Bioaccumulation by Different Macrophytes

Artisanal gold mining in West Africa generates acute metal contamination of aquatic ecosystems, with Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, and Hg concentrations far exceeding WHO standards. Nature-based technologies, such as phytoremediation, represent a sustainable alternative to reduce this pollution. This study evaluates the capacity of E. crassipes to bio accumulate heavy metals in a contaminated water body in Côte d’Ivoire, analysing accumulation kinetics and comparing its performance with other macrophytes. Physicochemical analyses conducted in this work revealed, for instance, a pH of 6.87±0.12, a COD of 1297±25 mg O2/l, and a BODO2 of 300±10 mg O2/l, confirming the severity of pollution. The experiment conducted on E. crassipes highlighted a strong bioaccumulation capacity, reaching 242.9±12.5 mg/ kg for Zn, 162.7±8.2 mg/kg for Pb, and 155.8±7.9 mg/kg for Cu after 6 w. The data show robust accumulation kinetics (R2>0.99 for BAF) described by the pseudo-second-order model (R2>0.998), with maximum equilibrium capacities (qe) reaching 661.66 mg/g for Zn and 442.95 mg/g for Pb. The GAI allowed classification of metals according to their extraction performance: Zn (54.1)>Cu (44.1)>Cd (43.1)>Pb (38.9)?Hg (20.0). This hierarchy suggests differentiated management: Hg, despite rapid kinetics, remains poorly accumulated, while Zn and Pb, strongly extracted, should be prioritized as targets for depollution. Ultimately, this study demonstrated that E. crassipes is a rapid and effective ecological solution for phytoremediation of water bodies contaminated by artisanal gold mining. However, its invasive potential requires confined use in artificial systems or constructed wetlands, ideally combined with other macrophytes for longterm ecological stabilization and secure storage of accumulated metals.

Conflict of interests:

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

References

- Hilson G, Hilson A, Adu-Darko E. Mining, poverty and development in sub-Saharan Africa. Extractive Industries Soc 2021; 8(1):100-12.

- Wadsworth A. Mercury use in artisanal gold mining and its impacts in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sci Total Environ 2023;857:159569.

- Abbas SZ, Huang D, Ullah H. A review on heavy metals uptake, toxicity and tolerance in plants. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020;27(18):22927-42.

- Lu X, Zhang Y, Liu J, Xu J. Phytoremediation potential of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) in heavy metal–contaminated waters: A review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021;28;32841-57.

- Goswami P, Sharma R, Singh A. Phytoremediation potential of aquatic macrophytes for heavy metal-contaminated water bodies in developing countries. EnvironTechnol Innov 2022;28:102623.

- Monroy-Licht A, González-Mendoza D, Carrillo-González R. Chelation and compartmentalization mechanisms in metal hyper accumulator plants: Recent findings and future directions. Plant Physiol Biochem 2024;204:107134.

- Kumar A, Sharma S, Singh RP. Modelling of pseudo-second order kinetics in heavy metal phytoremediation: A comprehensive review. Environ Technol Innov 2021;24:101873.

- Bayuo J, Agyeman PC, Nyarko BJB. Kinetics and modeling of heavy metal uptake by aquatic macrophytes: A case study with multi-metal systems. J Environ Manag 2023;345:118273.

- Eid EM, Shaltout KH, Al-Sodany YM. Metal uptake and accumulation by macrophytes in multi-metal contaminated wetlands: A comparative study. Chemosphere 2021;278:130366.

- Al-Baldawi IA, Abdullah SRS, Anuar N, Hasan HA. Phytoremediation of heavy metals by constructed wetlands: Recent trends and future prospects. Environ Technol Innov 2021;24: 101957.

- Wang W. Comparative study of heavy metal removal by groups of macrophytes. J Environ Manag 2021;279:111-45.

- Nyame FK, Armah TK, Obiri S. Ecological and human health risks associated with gold mining in Ghana. Toxicol Environ Chem 2012;94(6):1211-21.

- Ato AF, Obiri S, Yawson DO, Pappoe AN, Akoto B. Mining and heavy metal pollution: Assessment of aquatic environments in Tarkwa (Ghana) using multivariate statistical analysis. J Environ Sci Health Part A 2013;48(4):456-69.

- Bayuo J, Kumar S, Zhang L. Comparative uptake of heavy metals by aquatic macrophytes: Kinetics, mechanisms, and practical applications. RSC Adv 2023;13:12345-58.

- AFNOR (Association Française de Normalisation). Water quality-collection of French Standards. Paris (France); 1997.

- Benhassine H. Assessment of wastewater biodegradability using COD/BOD ratio. Environ Monit Assessment 2020;192:567.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 4th ed. Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality. 2017.

- Abbas T, Rizwan M, Ali S, Adrees M, Qayyum MF, Ok YS, et al. Phytoremediation of heavy metals by aquatic plants: Current trends and future prospects. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021;28(4):4095-109.

- Zhou, Q., Zhang, J., Fu, J., Shi, J., & Jiang, G. (2020). Biomass, root morphology, and heavy metal accumulation of Eichhornia crassipes in relation to sediment contamination. Ecol Engin 2020;143:105669.

- Pandey VC, Singh JS, Singh RP. Phytoremediation of multi-metal contaminated soils using aquatic plants: Recent developments and future perspectives. Chemosphere 2023;327:138425.

- Oladipo MA, Gazi M, Yilmaz M. Mercury adsorption mechanisms on plant-based biosorbents: A review. J Environ Chem Engin 2021;9(4):105358.

- Foo KY, Hameed BH. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem Engin J 2010;156(1):2-10.

- Yadav SK. Evaluation of Lemna minor and Pistia stratiotes for heavy metal removal from wastewater. J Hazardous Mater 2020;389:121920.

- Rezania S. Efficiency of aquatic plants for phytoremediation of heavy metals in wastewater: A review. Ecol Engin 2016;91-61-72.

- Hassan SH, Van Ginkel SW, Hussein MA, Oh SE. Comparative assessment of aquatic plants for heavy metal removal. Chemosphere 2020;246:125799.

): Limite cote D Ivoire; (

): Limite cote D Ivoire; ( ): Commune de Songon; (

): Commune de Songon; ( ): Site de prelevement and (

): Site de prelevement and ( ): Coure d’ eau

): Coure d’ eau

): Voie principal and (

): Voie principal and (

): Pb; (

): Pb; ( ): Cd; (

): Cd; ( ): Zn; (

): Zn; ( ): Cu and (

): Cu and ( ): Hg

): Hg

): Pb Exp; (

): Pb Exp; ( ): Cd Exp; (

): Cd Exp; ( ): Zn Exp; (

): Zn Exp; ( ): Cu Exp; (

): Cu Exp; ( ): Hg Exp; (

): Hg Exp; ( ): Pb Model; (

): Pb Model; ( ): Cd Model; (

): Cd Model; ( ): Zn Model; (

): Zn Model; ( ): Cu Model and (

): Cu Model and ( ): Hg Model

): Hg Model

): Zn; (

): Zn; ( ): Cu; (

): Cu; ( ): Cd; (

): Cd; ( ): Pb and (

): Pb and ( ): Hg

): Hg

): Pb; (

): Pb; ( ): Cd; (

): Cd; ( ): Zn; (

): Zn; ( ): Cu and (

): Cu and ( ): Hg

): Hg